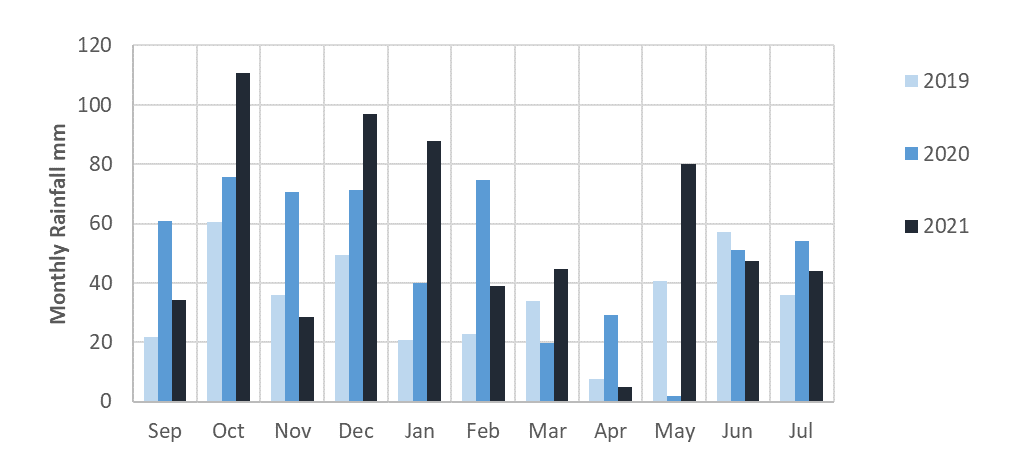

Whilst harvest of barley and oilseed rape has now started on many farms, it is up to three weeks later than was seen last year, which whilst frustrating, should be good for yield prospects. Initial reports are of barley yields generally being reasonably good. Most farms escaped the worst ravishes of the weather this season. September-sown cereal crops got away well, and have looked good all season, except where they are smothered in black grass or have lodged. The weather broke in late September with continuous rain meaning that many of those who sensibly waited to delay drilling to minimize the blackgrass threat were rewarded with a much longer delay than planned, often into less than ideal conditions. Thankfully, what felt like it might be a repeat of the disastrously wet 2019 autumn did eventually let up, and most planned autumn crops were eventually established.

Monthly Rainfall for Boxworth, Cambridgeshire, over the past three years. Data from DTN.

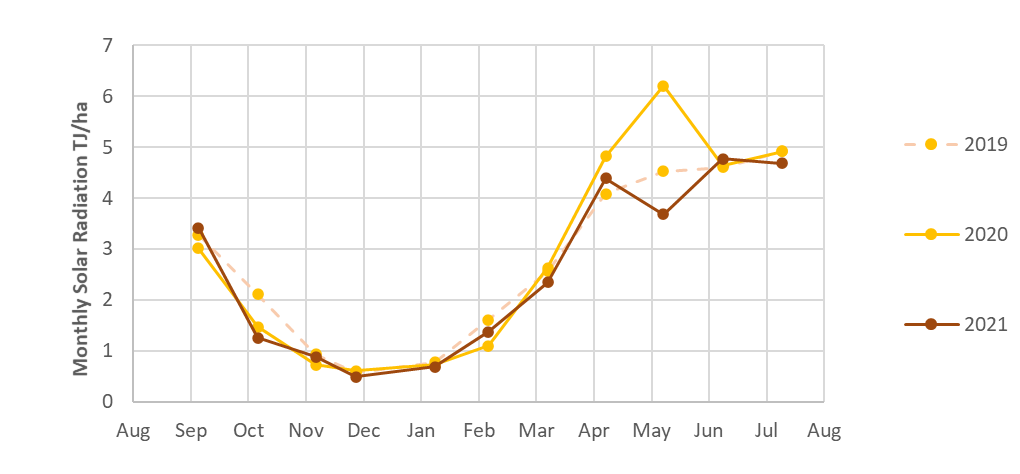

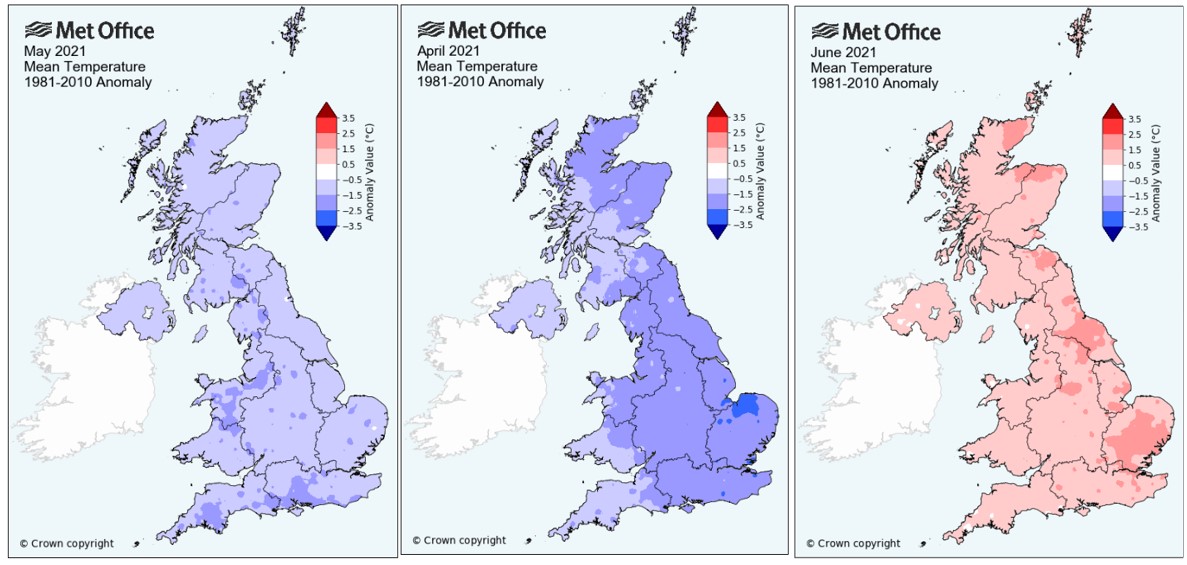

The spring of 2021 also began like the previous season, with a very dry March and April giving concerns about fertilizer uptake and tillering, though the rains came in May. The dry weather in April and prospect of stunted growth meant that PGR applications were perhaps reduced, or missed, the consequence of which is now being seen with lodging, especially in winter barley crops. April and May were both very cool, slowing crop development giving a long ‘construction period’ which should help with tiller production and retention. Whilst April was bright, May was very dull, especially compared to 2020. The cool conditions meant that ear emergence and flowering were late, with some wheat crops still flowering at the end of June. Perhaps of greater concern is that June was warm (see Met Office anomaly map below), without being bright. We have seen in the past that warm June temperatures can be associated with lower yields, in part because of higher respiration rates – this can be especially costly where canopies are large. Warm June temperatures also give faster development, which given the lateness of flowering, may mean that the grain filling period will be shorter than normal. Indeed the recent hot weather in July with temperatures exceeding 30C has hastened senescence in many areas.

Monthly Solar radiation for Boxworth, Cambridgeshire, over past three years. Data from DTN.

Temperature Anomaly maps (compared to 1981-2010 means) for April to June from the Met office

Disease pressure may play a more important role in yields this year than in recent years. Septoria tritici was slow to develop early on due to the cold, dry conditions through April, with crops looking very clean at T1 and many growers reducing fungicide inputs. However, the wet May saw conditions enabling the pathogen to spread through rain splash onto the top three yield forming leaves in a way which we have not seen for several years. Whilst there were a few weather windows enabling well timed T2 applications, the absence of chlorathalinol has hampered protection. The cool May slowed disease progress so crops continued to look relatively clean despite latent infections which appeared when temperatures increased in June. The apparent breakdown of resistance to Septoria of some varieties (Cougar parentage) adds to the likelihood of yield losses from Septoria this year, especially in susceptible varieties and early sown crops where T1s were reduced.

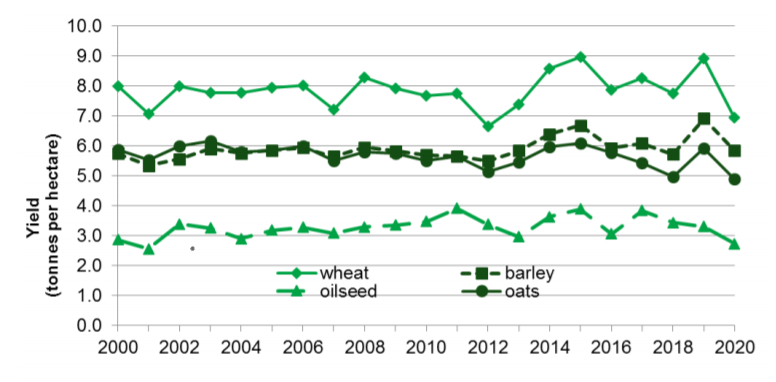

Using our simple biophysical yield model from the YEN the lower solar radiation levels in 2021 gives potential yield estimates well down on 2020 (>1 t/ha lower) where soils are not limiting for water. However, on droughtier soils (~150mm Available Water Content) the extra rainfall this year gives substantially higher potential yields than in 2020 (>1 t/ha). There is still a lot to learn if we want to be able to predict national yields with any precision, and ideally we need technology to track what is happening during the all-important filling and ripening phase of crop production. National yields have averaged around 8 t/ha for the past twenty years, with high yield of 9 t/ha seen in 2019 and low of 7 t/ha in 2020. Last year Agrimetrics set up a Yield 21 prediction competition using the Agora platform from Hivemind - the current prediction averages around 8.4t/ha.

National average yields over the past twenty years for major crops as published by Defra Farming Statistics

If you have an opinion on where wheat yields will end up, please sign in and post below.

Comments

I'm saying not above 8.2 t…

I'm saying not above 8.2 t/ha for national average yields in 2021.

Is anyone else brave enough to have a guess?

National average of 8.4t/ha …

National average of 8.4t/ha - I am being optimistic - Cool, wet May balanced against high disease pressure & warm, dull June. I suspect on drought prone soils yields could be pleasing but where yield potentials were high, the lack of bright conditions in June may leave some disappointed.

I'm going to hazard a guess…

I'm going to hazard a guess at 8.0 t/ha national average. Although crops established well I think the dull June and high disease pressure will have a big impact, in addition to the extremes of the weather experienced throughout the season.