Abbie Marshall & Kate Storer

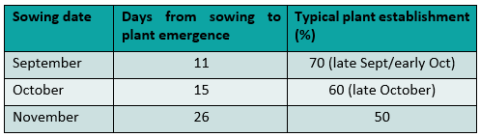

Tiller production is primarily driven by thermal time, assuming that water, disease levels and nutrients are not limiting. For winter wheat, it will take around 150oC days from drilling to emergence. Therefore, as temperatures begin to drop, it will take longer for crops to emerge and the percentage of seeds establishing viable plants drops. For September sowing dates, plant establishment is typically about 70% (Table 1), though this can vary by soil type. As drilling becomes later seed rates should be increased in line with reduced expectations for plant establishment and shoot number production.

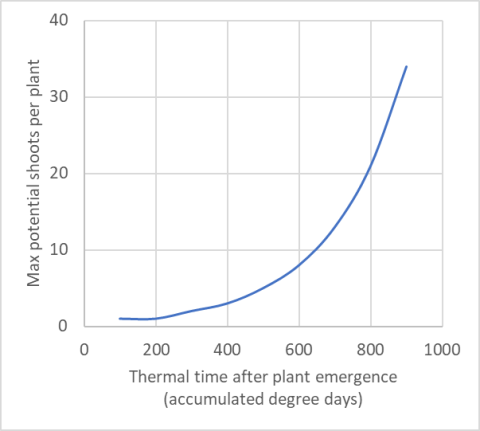

The phyllochron length is the time between emergence of successive leaves and is measured in thermal time above a base temperature of 0oC. For autumn drillings of wheat, it takes between 125 to 90oC days above 0oC, or one phyllochron, to produce a new leaf. Consequently, later sowing results in fewer leaves emerging on the main stem by stem extension because less thermal time is accumulated between plant emergence and GS30. We might expect eight to nine main stem leaves in late September/early October drilled crops, decreasing to five leaves for November drillings. Production of the first tiller from the main shoot occurs when the 3rd leaf of the main shoot has fully emerged. The 2nd tiller is produced when the 4th leaf of the main shoot has emerged. The 5th and 6th shoots are produced at the same time in the axils of the 3rd leaf of the main shoot and 1st leaf of the first tiller. This pattern of tiller production continues in a sequence known as the Fibonacci sequence as summarised in Figure 2 below. Of course, stresses such as low light levels, inadequate nutrition and competition with neighbouring plants mean that plants cannot support the production of all potential tillers.

If drilling is delayed by a month, an extra 50 plants/m2 are typically needed to compensate for the reduction in tillering potential arising from less thermal time between plant emergence and the start of stem extension (which usually signals the end of tillering).

Figure 2. Maximum potential number of shoots per plant.

Last season was a good reminder of the importance of maximising the number of tillers going into spring with tiller retention likely being reduced due to the dry conditions. So far this season we have seen favourable ground and weather conditions and many will be thinking of drilling their winter cereal crops early. In theory this should maximise shoot production for the coming season however, early drilling comes with its own challenges and considerations.

Soil moisture at drilling

So far this season we have received reports of crops with poor establishment from drilling in soils with a low moisture content. For September sowing we would usually expect a plant establishment of 70%, this will vary by soil type, with sandy soils generally having an average establishment of 90% compared with 65% on loams and clays. However, this relies on there being enough soil moisture for the seed to germinate. Rolling can increase seed to soil contact which can in turn increase water uptake by the seed in dry conditions. Wheat crops are able to compensate to some extent for poor establishment through additional tillering however, barley’s tillering ability is limited compared to wheat so it is important to consider the moisture availability at drilling to minimise these risks.

Variety

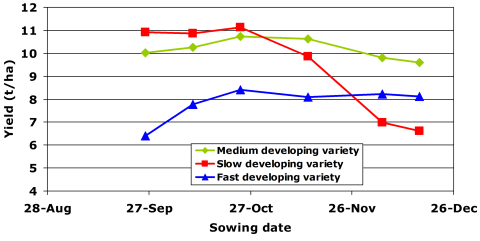

Variety is an important consideration if you are planning to drill earlier than usual. Figure 3 demonstrates how drilling date can have a large effect on final yield depending upon how fast a variety develops. Slow and medium developing varieties are best suited to early drill dates as they can maximise the number of tillers they produce without the additional risk of lodging and frost damage that faster developing varieties face. Targeting a variety with a low risk of lodging if you are sowing before the end of September is ideal. Sowing a crop one week earlier will reduce the effective varietal lodging resistance score by 0.5 points so it is important to stay on top of your PGR programme in the spring to reducing the chance of lodging.

Wheat bulb fly

The AHDB wheat bulb fly (WBF) project developed a scheme which predicts the optimal target plant population and/or sowing date for a given WBF risk (Crop management guidelines for minimising wheat yield losses). While this still needs further testing, it is important to consider in the absence of chemical options how early sowing, or an increase in seed rate, can be employed to minimise the risk of WBF damage.

Average yielding wheat crops (~8 t/ha) require a minimum of 400 fertile shoots/m2 at harvest, a target of 500 shoots/m2 remaining after WBF damage has occurred should therefore give sufficient insurance to achieve this yield. This should be increased to 600 shoots/m2 for crops expecting to yield 11 t/ha or more (Calibrating the wheat bulb fly threshold scheme using field data). Wheat crops often produce more shoots by GS30 than are required for typical yields, and it may be possible to take advantage of this to tolerate some pest damage, for example by WBF. The scientific literature suggests each WBF larvae can destroy about four shoots, and only approximately 44% of the eggs survive to produce larvae, so for a WBF egg count of 250 eggs/m2 (equivalent to 2.5 million/ha), this will mean 440 shoots/m2 could potentially be lost to WBF. For a crop yielding up to 11 t/ha, the target maximum shoot number would therefore be 940 shoots/m2. The scheme aims to estimate how many more plants/m2 would be required for a given drilling date, or how much earlier to drill for a given target plant population to produce a crop with the required shoot number. However, any increase in seed rate will need careful consideration of cost/benefits and the greater risk of lodging.

References:

Leybourne, D.J., Storer, K.E., Berry, P., Ellis, S. 2021. Development of a pest threshold decision support system for minimising damage to winter wheat from wheat bulb fly, Delia coarctata. Annals of Applied Biology. 180:118-131.

| ACTION · Adjust establishment percentages to suit the time of drilling as well as the soil type and moisture availability. · Increase the seed rate to achieve an extra 50 plants/m2 required if drilling is delayed by a month to compensate for the reduction in tillering potential. · If you are likely to have a high WBF risk, consider sowing earlier, increasing seed rates or using seed treatments for November sowings to help tolerate damage. · If you are planning to drill earlier than usual, ensure you have considered if the variety is best suited to early drilling and keep a close eye on lodging risk later in the season. |